“Water we come from, to water we may return.”

It snowed and snowed. Arthur’s Seat was so white, the sheep that grazed it nearly disappeared from plain view. Only their dun faces rescued them from visual oblivion. The crows on Crow Hill sleek-black in stark contrast, cawed and skipped over the cold layer, pecking at it in case it was a new kind of food. They should have known better for they’d been living and nesting here millions of years before human life. A murder of crows high on a hill, watching. Always watching.

Down below there was a new structure that they took an interest in, a low building of grey stone where people seemed to flock on a certain day of the week looking pious and talking in low voices, but which still seemed sibilant in the surrounding quiet. Sometimes they came here to bury their dead.

The crows knew about funerals for they too mourned their dead in their own way. Their shrouded appearance meant they were perfectly adorned for the ritual. And there was a great deal many more crow deaths in this 12th century after Christ as they were actively extirpated by legislation just like the wolves. The wolves hunted livestock and the crows picked at the corn seeds. Neither were popular among the human population who were very superstitious and believed both to be representatives of some evil superhuman force: the de’il or Auld Hornie.

The crows, like the kites and the rooks, the buzzards and mittels had the good fortune to be able to rise above this dark land of forest and swampland. They could fly over the loch which stretched all the way to Blackford Hill. They would not fly to the town of Edinburgh for that was not their world. The birds up at the Castle Rock seemed sturdier and far more street-wise, fiercely protective as they were of the juicier pickings available to them. The crows of Crow Hill appreciated the cleaner air outside the town. Edinburgh reeked of peat and wood smoke and was acrid from the combined smell of too many humans and their excretions.

The moon is as old as time and the folk around the glebe ignored it much like folk had been doing for centuries. It shone its light then it disappeared behind clouds and re-appeared as the day grew dark. The moon was the lantern of the poor.

The dwellers on the loch were no astronomers. Their cosmos was their very immediate surroundings. They fished for carp and pike from the loch, and they rowed ashore in shallops and coracles to hunt for meat. Such people had little to do with agriculture at this time except to trade for barley for the family broth. The loch was shallow, about ten feet down and they were able to drive piles down into its bed – the local ash trees were strong and durable – and erect huts big enough for a small family to dwell. Thus, they were safe from wolves in the night and human predators who may want to steal from them or injure them in some way. These were harsh and violent times. Land-grab and property theft (whatever there was of it) were commonplace occurrences and one was better planted out on the loch out of harm’s way than in the dark woods.

A life full or deficient? Hard to tell when you don’t know any better. A harsh and relatively short-lived existence with death and disease a daily presence. Imagine a winter in such a landscape and the relief of a milder summer.

Where else is happiness in this darkest of worlds but from relief and – for some, at least – belief? An unforgiving yet Christian world. What passes for consolation in a world where the elements are against you? A God in heaven? A butterfly on a leaf? These people fought and cried and fell in love. They had their stories and folktales. They made tools and weapons. They made utensils and ornaments. They were creative because they had to be and because they wanted to be.

A violent world of land-grab and feud, and a diet of sheep’s heid broth. And were there really bone bridges made from sheep’s skulls and what were they for? A rite of passage? Some funereal or religious ceremony? Certainly, sheep’s skulls were utilized as cobbles on the street. One walked on dead skulls. There were sheep’s heid’s everywhere. The whole area was a slaughterhouse for sheep. The sheer, dark bloody viscosity, you could smell it in the air. It was the only rival for dung. Dung and blood and Dodinston.

If there ever was an ‘age of innocence’ it is by now long past. Heavenly bliss, they are told, is in the afterlife and down here one must prepare for it by living decently and kindly to others. There were those though, seemingly so sure of their place in the Lord’s heavenly manor that they took what they could for their earthly comfort regardless.

And now they had a church next the loch but what good was that to simple folk who couldn’t even understand the Latin liturgy or read whatever was written about ‘their saviour’. It seemed to them that Christ was for the poor but only the well-to-do were welcome for the preaching of him.

Jenny Spence offers her face to the darkening sky and lets the rain splash on her eyelids. The cold freshness of it makes her feel fully alive in her seventeen years. She likes to roam the slopes and crenellations on Arthur’s Seat. She loves the yellow gorse and engages with the sheep as if they can understand her meagre vocabulary then laughs at her silliness. She looks out and beyond at the blue-purple hills in the far distance and wonders if lives like hers are lived under those slopes. Is this the full extent of the whole world? She has heard tell of other lands even further away. That there are other lives and other possibilities she is well aware. The goodly folk in her own small community, the ones that must be deferred to, are clothed more richly and more warmly it seems. Their food is of better quality and more carefully prepared.

Married at thirteen. Her ‘man’, Joseph, all of fourteen was from somewhere he called Walter’s Kyle by a river in the west of the land. He is now all of seventeen and walks the miles each morning to Musselburgh to catch shellfish. Hers was a ‘handfast marriage’ meaning she was married according to secular custom and not under the matrimonial edict of the church. She wore a brooch fashioned from pewter to commemorate her wedlock. She did not know of ‘churches’ until only recent months when the new building appeared and along with it the new rules and regulations about who was allowed to go where and who most definitely was not.

She risked the glebe in her search for hazelnuts to roast. It was marshland wild and mulchy waiting to be cultivated into a garden suitable for the new church. Suitable for its clergy. Jenny liked its wildness, the high stalks, its weeds and wild grass. She liked to smell the bog myrtle. She felt she could lose herself in it and wasn’t at all looking forward to its trimming and taming. Sometimes the otters foraged in its undergrowth and pools looking for whatever otters looked for.

And yet, it was all going to change. The coming of the church meant this glebe-land would take on a different shape and texture altogether. ‘A garden of the spirit’ was how it had been described by the local monks from Prestonfield beyond and new walls were to be built to make it exclusive to religion and some of the local worthies and high heid yins from Kelso.

Jenny liked to climb to Dunsapie Loch for her chore was to carry in a sack the fresh water from there. It tasted to her of rain and did not have the brackish quality of the water in her own loch. It was also true that folk were too superstitious to drink from the big loch for they knew of the recent tragic history of the little twins that had drowned in it. They feared the decomposition going on down there among the sedimentation and pondweed. No-one wanted to drink the effluence of dead flesh. And how many more dead were down there never mind that sheep flesh was steeped there to keep it from going bad.

“You’d be quenching on blood and bones,” was what she told Joseph whenever the subject came up.

Jenny imagined a freak drought when the loch lost all of its water to the sky and there at the bottom the bleached bones of the boys (and how many others?) along with a million sheep’s skulls. She preferred the land where the dead were at least buried and out of sight. They were buried on the slopes of Arthur’s Seat if they were from ‘the common fowk’ and maybe under a cairn if they were high and mighty and a local baron may have a mausoleum for they and their family to rest in.

She felt her only friends and her best confidantes were the crows. She had a feeling of kinship with them that she didn’t feel with her neighbour’s on the loch or in the dark village. She had married an ‘outsider’ and ‘not in the church’ and she was shunned for these indiscretions. She would talk to the crows and ask their advice.

“Water has a memory,” she told them, and they seemed to stop to listen “for it never disappears,” and “The lichen on the rocks is healthy and good for my monthly cramps.”

The crows of course could never be expected to understand the words, but they were good on sentiment and Jenny brought them oats and course bread, so they gave time for her ramblings.

She gazed down at the glebe and the loch and then turned to face the sea.

“They say men of violence have sailed to these shores from lands too far to see away to the east!”

The crows cawed and croaked in incomprehension.

She gazed down at the Wells o’ Wearie which were another water source and, Jenny believed, a place of magic. She wrapped her plaid shawl more tightly around her as the breeze atop the hill freshened enough to blow her brown hair across her pretty face. She believed she was with child and the conception had been at the wells.

You’ll see crow-friends that my child will be special!”

She left the crows to think of a gift fit for such a child.

The Reverends Wife

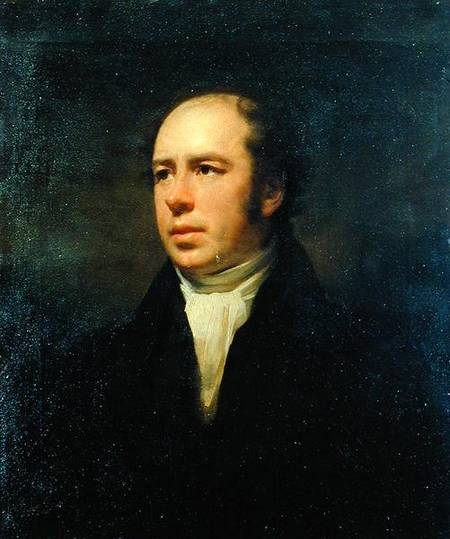

The man that chases along the Windy Gowl on his way home is a man of some eminence: a personage in this dark, roguish city of Edinburgh. He is the Reverend John Thomson who occupies the manse at Duddingston Kirk with his lovely and loving second wife, Frances and their ‘three families’.

“That’s my family; that’s John’s family; but these (pointing to the youngest) are ours!” is how she welcomes guests to the now extended manse (extended because it was now home to so many social occasions and, of course, due to the three families).

The Revd Thomson is ‘chasing home’ because, once again, he is late for an appointment. He had found an aspect of light pouring over Arthur’s Seat that he just had to paint and he’d rather lost track of time. Frances doesn’t fret because she knows her husband well and, anyway, she is gracious and cordial enough in her own right to entertain their guests until her husband’s arrival.

And what guests they were! One could not have homely society more convivial. Even the morose Turner could not injure the jollity. The celebrated English painter was a great lover of the area and the dramatic and bucolic landscapes it offered. He would stand on the glebe, on the very banks of the loch with his claret in one hand, cigar in the other and gaze at the impressive vista of loch and mountain and the Pentland Hills in the distance and exclaim to the good Revd come to join him as the crepuscular twilight slowly dwindled to shadow…

“By God, though John, I envy you that piece of water!”

To which the good minister would respond with warmth and sincerity for he loved and respected the gruff master…

“You may have it, Joseph, you may have it!”

And Sir Walter was here too along with Grecian Williams and The Ettrick Shepherd himself, James Hogg, flushed with the success of his new book and its instant popularity.

The manse was renovated to cater for the large family and the society the good Reverend engendered. New rooms for children and for the entertaining of guests. Yet, the reverend was not a frivolous or wasteful man. He was the son of a minister from Dailly, Ayrshire. The son of a preacher man, yes, he was. His brother was a man of the legal profession who knew Sir Walter Scott and then Scott promoted John Thomson though a mere 23 to be minister of the manse at Duddingston. A good man for the job, this devotee of science and art and God.

The Reverend had no time for the pious or the prudish. Churchly proprieties aside he liked a good gossip so long as there was no malice in it and, like his Master of Nazareth, his best attentions were for the poor and humble of means and there was no shortage of those in his parish. The parish of Duddingston and Portobello contained the well-heeled, the fairmer, and the salt-working labourer.

Auld Betty Steele from the dairy on the hill had asked him for a prayer. Instead, he’d slipped her a useful coin…

“Tak’ that, Betty, my good woman; it’s likely to do you more good than any prayer I’m able to make!”

There’s no doubt he’d have kept her in his prayers in any case.

The whiteness of the ice and the steam coming from the brushers as they cleared the way, brushing with all their might, for the heavy stone. The reverend loved his curling and loved equally the socializing with friends back at the manse and its extensive garden. The loch is smaller now, ten times smaller. Land has been developed, the parish is bigger and includes all the Abercorn Estate, Wester and Easter Duddingston down to Portobello, Joppa, Magdalene Bridge. The loch freezes over and is famous for its winter sport. Scenes from Brueghel as the brushers and curlers pursue their leisurely competition and spectators fill the glebe and the odd hip-flask with malt whisky. There is a nip in the air, and no one wants a seasonal chill.

Frances Ingram Spence is the good reverend’s second wife, the first, Isabella Ramsay, having died suddenly in 1809 two weeks after having given birth to a daughter named after her. She sees a Thomson painting in an Edinburgh art shop and wants to meet the artist. For Thomson it is love at first sight. “That woman must be my wife,” is what he says.

Frances was the sun and John Thomson thrived on her energy. Her first husband, Martyn Dalrymple, had been lowland aristocracy but he too had died in 1809 still a young man.

So, both Frances and John had known marital grief, and each had been left alone with young children. What solace and joy, then, for each to have found such love and tenderness in one another.

After the curling there is music. And as the reverend plays something amusing on his violin for his assembled friends, Frances gazes from the manse out onto the gardens and the loch.

This is such a happy place, she thinks, but she wonders was it always?

Scott was reciting as he often did when perky with good claret.

“It was a night of lovely June

High road in cloudless blue the moon!”

“Ach, Wattie, sit on yer auld erse, and enough o’ yer shilpit sentiments!”

This from Thomas Dick Lauder for they were all old friends and affectionate ribbing only added to the general conviviality.

Manse, glebe, loch and the moon rising above an old volcano. Both grief and love had brought he to beauty.

Jock Tamson’s Gairden

“I wonder if you could write something about The Glebe. You know, the story of it through the ages type of thing?”

So said the manager of Jock Tamson’s Gairden to me one bright morning in late winter with the sun shining on Duddingston loch. Maybe she didn’t know that, as a Spence, she was likely related to this place of religion. A ‘glebe’ is the Scots word for a garden connected to a manse. The manse’ in question being at Duddingston Kirk in the bucolic wee hamlet at the very foot of the north-east heights of Arthur’s Seat. It has been known as The Glebe for centuries but only recently, this past couple of years, has its name been Jock Tamson’s Gairden.

This appellation is in commemoration of the old Scottish saying ‘We’re aw Jock Tamson’s Bairns’, an egalitarian affection which may well derive from the time of the kirk’s most famous Minister, the Reverend John Thomson, who reputedly referred to his congregation as his ‘bairns’ (folk in Buckhaven will dispute this and claim that the saying was due to a philandering Fifer who is the principle reason, they would claim, that there are so many ‘Tamson’s’ in the local phonebook).

Lizz was charged with the development of this pretty four and a half acres and is the reason, along with the efforts and talents of a hearty band of committed and talented volunteers, why the gairden is in the fine form it is today.

And speaking of the volunteers. Why were they all named Ian? Even some of the women were so named, or so it seemed.

“Mornin’ Ian!”

“Aye, it is that Ian!”

“Is it yourself, Ian?”

And on and on it went until the only person left to greet was Lizz and not another Ian.

This writer, to be fair, is not called Ian either, but he had the unfortunate habit of bothering Lizz when she was at her busiest sowing salad or erecting polytunnels or whatever it was gardeners did (this writer had not one clue about gardening, but loved it just the same. It seemed so…natural).

“Away and write something, Dave. Yer standing on my brassicas!”

Not being a man to tamper with a ladies’ brassicas over-long I go to the peace-bench under the old walnut tree to sit down and ponder what to write. This walnut tree was planted in 1805 when wood was needed for guns against the French. That was also the year the Reverend Thomson was appointed. Was everything about this place poetry and serendipity?

I gaze over glebe and loch and on the far bank is the Bawsinch nature reserve and think ‘What a fine place!’ I watch the Canada Geese flying in their formations, nature hard-wired for the long journey. I think of the Reverend Bennet who preceded John Thomson and who sadly died in this loch aged only 42. His passion in life had been the natural world of these parts; the fauna and flora to be found in this rich, fecund area. He identified in his scientific way the Reed Grass and the Marestail, the Tufted Duck and the occasional quail. He may even have been expert in the breeding habits of the Sedge Warbler.

The volcano and the glacial erosion which created the loch lives on in the soil in the parent rock and the clay. There are two gardeners now employed on the glebe. Their job is to look after the soil, to enrich and cultivate it. The physic garden that is Dr Neill’s is a notion going back to the 12th century when the church first occupied this land. A ‘garden of the spirit’ it was always meant to be. Jock Tamson’s Gairden is a new affair, only a couple of years old and you wouldn’t recognize the place from when Lizz took over.

She and her willing helpers have turned the garden from a muddy, weed-strewn broth into the picture it is today. The inflorescence is admirable. Broad beans, leeks, edible flowers, asparagus, sowing salad, carrots, coriander, dill. UPMO, the charity for adults with learning disabilities and autism, have a new polytunnel in progress. There is brand new decking decking outside the bothy constructed by community services, a splendid esplanade patio where folk can sit and gaze at the loch, the Latvian chapel is almost completed, the peace path designed by primary five kids, U3A have allotments and a choir to sing at this year’s garden-o-thon. The place is prim, productive and pretty and there’s even a big volunteer chap who will give a tour to interested visitors.

The crows are still watching from their hill and from the branches of the trees in the glebe. Of a sudden, as if delegated, a young crow – a corbett – swoops down and lands assuredly some yards from Lizz’s feet. From his beak he drops a gift for her.

It is a brooch of pewter from long, long ago.

David Wylie